In Sync: Inside the Mind of a Fighting Fish

Just beyond the doors of Columbia University, I watched two fish engage in a silent, synchronized standoff. Their fins flared like fans, their bodies shifting in a rhythm that felt almost choreographed. These weren’t just any fish. They were Betta splendens, also known as Siamese fighting fish—vivid, elegant, and full of unexpectedly complex social behaviors.

One can imagine aggression as an innate, yet simple, impulsive behavior—something raw and reactive. But Betta fish showed me otherwise. They revealed that aggression can be a kind of language—ritualized, deliberate, and deeply wired into the brain.

A Ritual, Not a Brawl

When two Betta fish meet, they don’t immediately lunge or bite. Instead, they rise—literally—elevating together in the water column as if acknowledging each other's presence. This begins an intricate ritual: fins flared, bodies turned, and subtle tail flicks exchanged in a measured, deliberate rhythm.

This isn’t chaos—it’s choreography. The fish coordinate their displays, sometimes escalating with synchronized tail beating, a sign that things may soon turn physical. But even then, it’s a form of communication. A negotiation. A ritual, not a brawl.

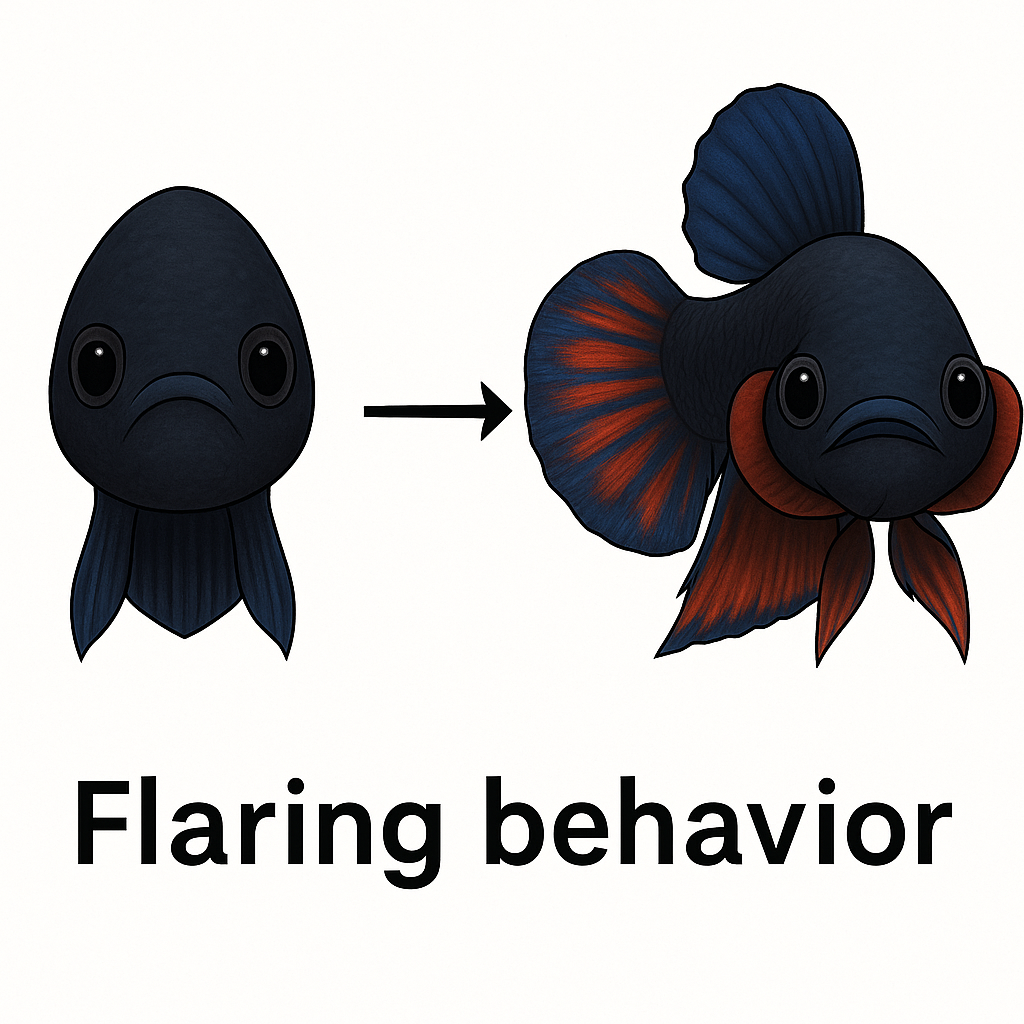

This ritualized display isn’t just mesmerizing—it’s measurable. One of the clearest and most widely used methods to study aggression in Betta fish is by quantifying flaring behavior, in which a fish extends its gill covers in a striking attempt to appear larger and more threatening. This fascinating behavior raised new questions. How is it coordinated? What cues drive it? And beyond what we can see on the surface, what brain regions and molecular mechanisms control and sustain these moments of ritualized aggression?

To truly understand Betta aggression, we needed a way to measure it precisely, maintaining the same context and signals across many individuals. To do this, our lab built digital fish. Using carefully designed animations, we projected virtual Bettas onto screens and watched how real fish responded. And they did respond—just as intensely as they would to a live rival. By showing every fish the exact same display, we could directly compare their reactions—including flaring, rising, and tail flicking—and capture subtle differences in how aggression unfolds across individuals. But what was going on in the brain to make this unique, ritualized behavior possible?

The Brain Region That Keeps the Fight Going

In the lab, attention turned to a region called the caudal dorsomedial telencephalon, or cDm—a part of the Betta brain that resembles the human amygdala, often described as the brain’s emotional amplifier. When this area was removed, something interesting happened: the fish still initiated aggressive displays, but the ritualized back-and-forth faded much more quickly than usual. This result suggests something powerful: the cDm doesn’t seem to initiate aggression, but it helps sustain it. In other words, it appears to keep the fish in the emotional and motivational state needed to remain engaged, even when things get tough.

Studying these fish offers a unique opportunity to dig into the molecular pathways that underlie aggression. The goal of this research isn’t to eliminate aggression, as it’s an innate, powerful response that can play a vital role in survival. Instead, by understanding aggression’s biological roots, we hope to better understand how these behaviors are regulated and expressed. This is particularly relevant in humans, as many neurological or psychiatric conditions—such as schizophrenia or certain forms of autism—can involve challenges related to aggression. In these cases, aggressive behavior may be difficult to regulate, both for the individuals experiencing it and for those supporting them. Unpacking the underlying biology may help inform more effective, compassionate interventions.

The Rhythm of Aggression

Betta fish have a way of holding your attention. Their movements and interactions are so precise and expressive that you can find yourself captivated by every shift and signal. What we observe isn’t just reflex—it builds gradually, unfolds over time, and fades slowly. These dynamics are strikingly familiar: aggressive behaviors in humans and other animals don’t erupt instantly. Internal states—like arousal or motivation—can shape how long they last, and how far they go.

So, what’s the takeaway from all this?

Next time you see a Betta fish in a pet store, take a moment to watch. You might be seeing one of nature’s most fascinating conversations. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that even a tiny fish can teach us something profound about how complex behaviors emerge—both in their brains, and perhaps in ours too.

The original research discussed in this post can be found in this paper: “Coordination and persistence of aggressive visual communication in Siamese fighting fish.” (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211124724015596).

Paula Rodriguez Villamayor, PhD is a Fulbright Postdoctoral Researcher at the Zuckerman Institute at Columbia University (CU), where she studies the neural and molecular basis of aggression using Betta splendens (Siamese fighting fish) as a model. Her research focuses on how complex social behaviors are encoded in the brain, with an emphasis on uncovering the molecular pathways and neural circuits responsible for behavioral changes.

Originally from Spain, Paula combines behavioral neuroscience with advanced experimental tools to better understand the biology of social behaviors. She currently serves as President of the Columbia University Postdoctoral Society, dedicating much of her time to supporting the postdoctoral community through resources, programming, and advocacy. She is also actively involved in science outreach, including CU’s Saturday Science program and BioBus events.

Outside the lab, Paula enjoys traveling, spending time in nature, and is currently training for the NYC half marathon.

Edited by Lauren Vetere, PhD